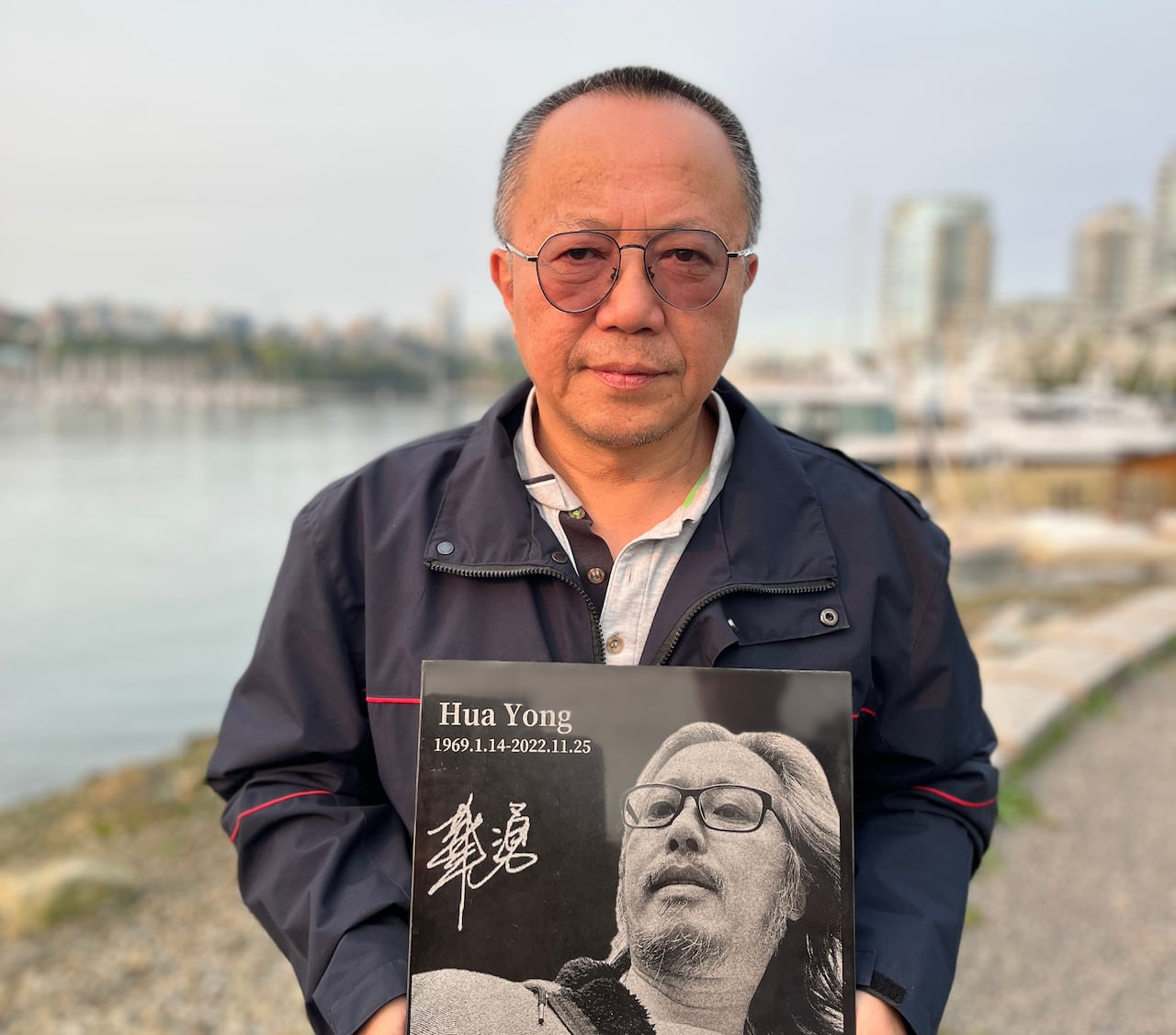

A former operative for China’s security services has come forward with a trove of documents, including thousands of text and voice messages, and financial records, offering an unprecedented look into Beijing’s covert global operations. Among these revelations are directives instructing him to monitor a Chinese artist who sought refuge in Canada, whose mysterious death in British Columbia in 2022 is now being called into question by the former spy.

Former Spy Details Surveillance of Dissident Hua Yong, Whom Authorities Wished to ‘Deal With’

Known by the pseudonym “Eric,” the man, interviewed in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, revealed his 15-year career as an agent for China’s secret police, spanning from 2008 to 2023. “My real job was to work for China’s secret police. It’s a means for political repression,” Eric stated, emphasizing that the primary targets were dissidents critical of the Chinese Communist Party.

Eric provided journalists from the Australian Broadcasting Corp., the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (a partner of CBC/Radio-Canada), and Radio-Canada with a wealth of incriminating evidence. These materials, which include financial transactions, secret money transfers, and the identities of other spies, illuminate the clandestine methods employed by China in its overseas intelligence activities. Eric agreed to be filmed and photographed but requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, a concern echoed by his Mandarin interpreter.

Eric explained that he was initially a pro-democracy activist, involved with the underground Social Democratic Party of China, before being coerced into intelligence work following a police visit. For a decade and a half, he served the 1st Bureau of China’s Ministry of Public Security, a division dedicated to monitoring dissidents abroad. His prior assignments, as reported by the Australian Broadcasting Corp., included spying on a Japanese cartoonist and an Australian-exiled YouTuber. He often operated under the guise of working for legitimate companies in host countries, which secretly collaborated with China’s intelligence apparatus. CBC/Radio-Canada largely corroborated Eric’s assertions using his archived phone data.

In 2020, Eric received orders to track Hua Yong, an outspoken artist and staunch critic of the Chinese Communist Party, who eventually settled on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast. The Chinese Embassy in Ottawa did not respond to inquiries regarding these allegations.

Befriending the Artist Online

Hua Yong’s history of dissent was well-known; he was arrested and sent to a re-education camp after a 2012 Tiananmen Square protest and again in 2017 for documenting mass evictions in Beijing. By March 2020, Hua had fled to Thailand. Chinese authorities, unable to reach him there, instructed Eric to entice Hua to Cambodia or Laos, nations with strong ties to China.

Eric’s handler conveyed this mission via a voice message on one of the many encrypted messaging platforms they utilized. Among the thousands of communications Eric retained, his handler’s Mandarin message regarding Hua was particularly chilling: “Listen to my request below. It’s about Hua Yong. The higher-ups find him quite annoying and want to deal with him.” This phrase could also be interpreted as “want to get rid of him.”

Eric discussed various strategies with his superiors to lure Hua to a country where China’s secret police could apprehend him. His chosen tactic involved initiating contact with Hua on social media, then migrating to encrypted apps. On Telegram, Eric proposed establishing a resistance group to garner support.

Messages Between Former Chinese Spy ‘Eric’ and Chinese Dissident Hua Yong

A text conversation between a Chinese ex-spy and a dissident who fled to Canada in 2021.

| Eric: | Brother Yong? |

| Hua Yong: | Yes? |

| Eric: | Did you go back to your home country? It’s very dangerous! |

| Hua Yong: | I’m still in Thailand. |

| Eric: | After our last conversation, I’ve been thinking about the first step you mentioned. … We can go to the jungle, or a nearby forest to save costs, gather some friends, put on camouflage… and make a “jungle livestream” to attract attention and gain more followers. |

(CBC)

Elaborate Deception: The ‘V Brigade’

To cultivate Hua’s trust, Eric fabricated an anti-Communist insurgent group called the “V Brigade,” promoting it across social media. In a September 2020 YouTube video, Eric, clad in a balaclava and camouflage, fired blanks while announcing: “Hello, everyone. I’m here with V Brigade to introduce today’s topic: How to individually prepare for armed revolution and armed struggle.”

The deception proved effective. “This is awesome!” Hua enthusiastically messaged Eric, and the two began collaborating as supposed revolutionary comrades, even meeting in Bangkok. However, in early April 2021, Chinese intelligence lost track of Hua, prompting a frantic search. Eric reported to his handlers that Hua seemed to have travelled through Turkey to Paris. On April 6, Hua announced on social media that he was in Canada, inviting Eric to join him and become a spokesperson for a new revolutionary group. Eric’s superiors, however, ordered him to return to China and monitor Hua remotely.

Unanswered Questions in Hua Yong’s Death

Hua Yong settled in Gibsons, B.C., where he pursued crab fishing and kayaking, as documented on his own social media. In the autumn of 2022, a near-capsizing incident involving his kayak and a passing luxury yacht was dismissed by Hua as a simple accident. However, for Li Jianfeng, a former Chinese judge now a refugee in Canada, it appeared ominous. “For him, this was a mere accident. But to me, it looked like an orchestrated murder,” said Li, who assisted Hua in his escape to Canada.

Weeks later, on November 25, 2022, Hua embarked on another paddle and never returned. His body was discovered on the shore of an island off the Sunshine Coast after an overnight search. At the time, the RCMP concluded there was no foul play, seemingly unaware that Hua was a target of a clandestine Chinese intelligence operation.

Li Jianfeng, referencing his experience in China’s justice system, expressed deep skepticism. “I fully understand the modus operandi of the Chinese Communist Party. They would stage an accident to murder someone. Yes, I don’t have direct evidence to prove his murder.” Li compiled a dossier with various leads and submitted it to the RCMP.

Canada’s former ambassador to China, Guy Saint-Jacques, urged that no possibility be dismissed, stating, “China’s regime has no shame and doesn’t hesitate to use brutal means to attain its objectives.” Eric himself believes other informants were likely monitoring Hua in Canada. “Based on the Chinese police’s commonly known operating methods, the party definitely has other agents in Canada, including spies or other special operation teams,” he asserted. “I’m almost certain of this.”

Spy Seeks Asylum and Public Protection

After multiple unsuccessful attempts, Eric finally fled China in 2023. Though he initially sought asylum in Canada, he obtained a tourist visa for Australia, where he now resides. Eric believes the world deserves to know about China’s covert police activities, seeing his public disclosures as a form of self-protection.

The official investigation into Hua’s death remains open, with the B.C. Coroners Service report still outstanding three years later, far exceeding the typical 16-month timeframe. Eric, while not having directly contacted Canadian police, confidentially submitted relevant documents to the Hogue commission, Canada’s public inquiry into foreign interference. “There are some strange aspects to this case that demand further investigation,” he concluded.